Ever had an experiment fail and wondered whether it was the buffer, the protocol, or something else entirely? Before you torch the protocol, there is one thing you need to check properly: the recombinant protein.

A faulty protein can render a perfect protocol ineffective, as incorrect reagents can cost you time, money, and patience. When you buy recombinant proteins, you’re buying a tool; pick the wrong one, and you’ll spend weeks troubleshooting something that never had a chance.

This guide tells you what actually matters. Get these basics right, and your results stop being unpredictable.

What are recombinant proteins — fast version

They’re proteins produced by a host cell engineered with the gene you want. You hand a cell the “recipe,” and it bakes the protein. That gives you:

- Purity (less cellular junk)

- Consistency (same batch next month)

- Scale (enough for actual experiments)

In other words: clean, repeatable reagents — if chosen correctly.

Four things to check before you click “add to cart”

Not every recombinant protein is fit for your purpose. Look for these on the datasheet.

1. The Host System

Where was the protein made? The host organism is critical because it determines how the protein is folded and modified.

- E. coli — fast and cheap. Good for simple, non-glycosylated proteins.

- Yeast — some eukaryotic PTMs, still affordable.

- Insect cells — better folding and PTMs for mid-complexity proteins.

- Mammalian (HEK293, CHO) — Best for sensitive functional work, but more expensive. Best match to human proteins.

Rule of thumb: For assays needing native folding or human-like PTMs, E. coli expression usually won’t cut it.

2. Purity and Formulation

Higher is better. You’ll see purity listed as a percentage, such as>90% or >95%, by SDS-PAGE.

Why? Because the impurities aren’t just filler. They can be:

- Endotoxins from bacterial hosts, which can cause immune responses in cell-based assays.

- Other host cell proteins that might interfere with your experiment.

Look at the formulation buffer. Is it plain PBS, or are there stabilizers, such as glycerol or detergents? Whatever it is, ensure it won’t interfere with your downstream application.

3. Is It Actually Active?

Biological activity is everything. A protein can be pure and look perfect on a gel, but if it’s misfolded or aggregated, it’s useless.

To provide proof of activity, the datasheet could be:

- An enzyme kinetics assay (e.g., measuring specific activity).

- A binding assay (e.g., ELISA or SPR).

- A cell-based functional assay.

A band on a gel doesn’t tell you anything if the protein isn’t active.

4. Tags and Their Troubles

Fusion tags (such as His-tag or GST-tag) are excellent for purification and detection. But they can also be a problem. A bulky tag on the N- or C-terminus can sometimes:

- Block active sites.

- Prevent proper folding.

- Interfere with protein-protein interactions.

If you’re doing sensitive functional studies, look for a tag-free protein or one where the tag has been cleaved off.

An Example of Choosing The Right Recombinant Protein

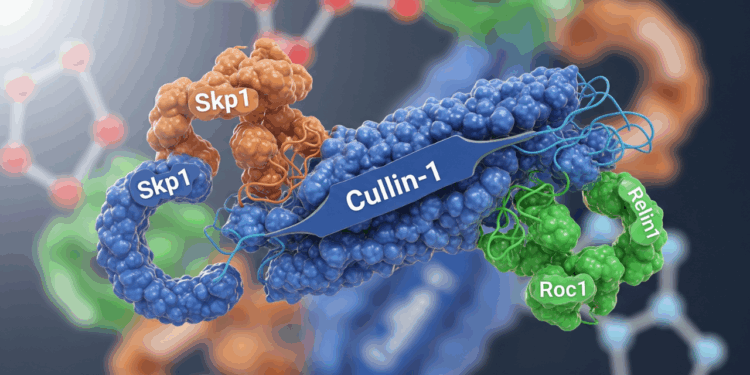

Studying ubiquitin ligases? For example, Cullin-1 Recombinant Protein needs correct folding and partner binding. Using our checklist:

- Check the Host: You might need a protein from an insect or mammalian system to ensure proper structure, for complex reconstitution assays, but for basic binding studies, an E. coli-expressed protein might be fine.

- Purity: To avoid other proteins interfering with your ligase complex assembly, you’d want a greater than 95% purity .

- Activity: Data showing it binds Skp1/Roc1 — no binding data, no sale.

- Tags: If tag blocks interaction surfaces, get a cleaved or tag-free prep.

Short-term savings aren’t worth long-term experimental headaches. Choose the recombinant protein that actually works for your experiment.

Finally…

Fully read the datasheet before you shop for your next recombinant proteins, as it can save you tons of money and time.

Ask yourself: Does the datasheet actually prove what I need? Does it show the activity, the purity, the host that makes sense for my work?

If yes, great — order it. If not, move on to find the right one. It may feel like extra effort now, but you won’t be doing your whole experiment on a questionable reagent.

Discussion about this post